Sanctuary of Fantasy: About

Here, a review is not a handful of words—it is a journey across worlds.

With tens of thousands of words, we unravel the souls of characters;

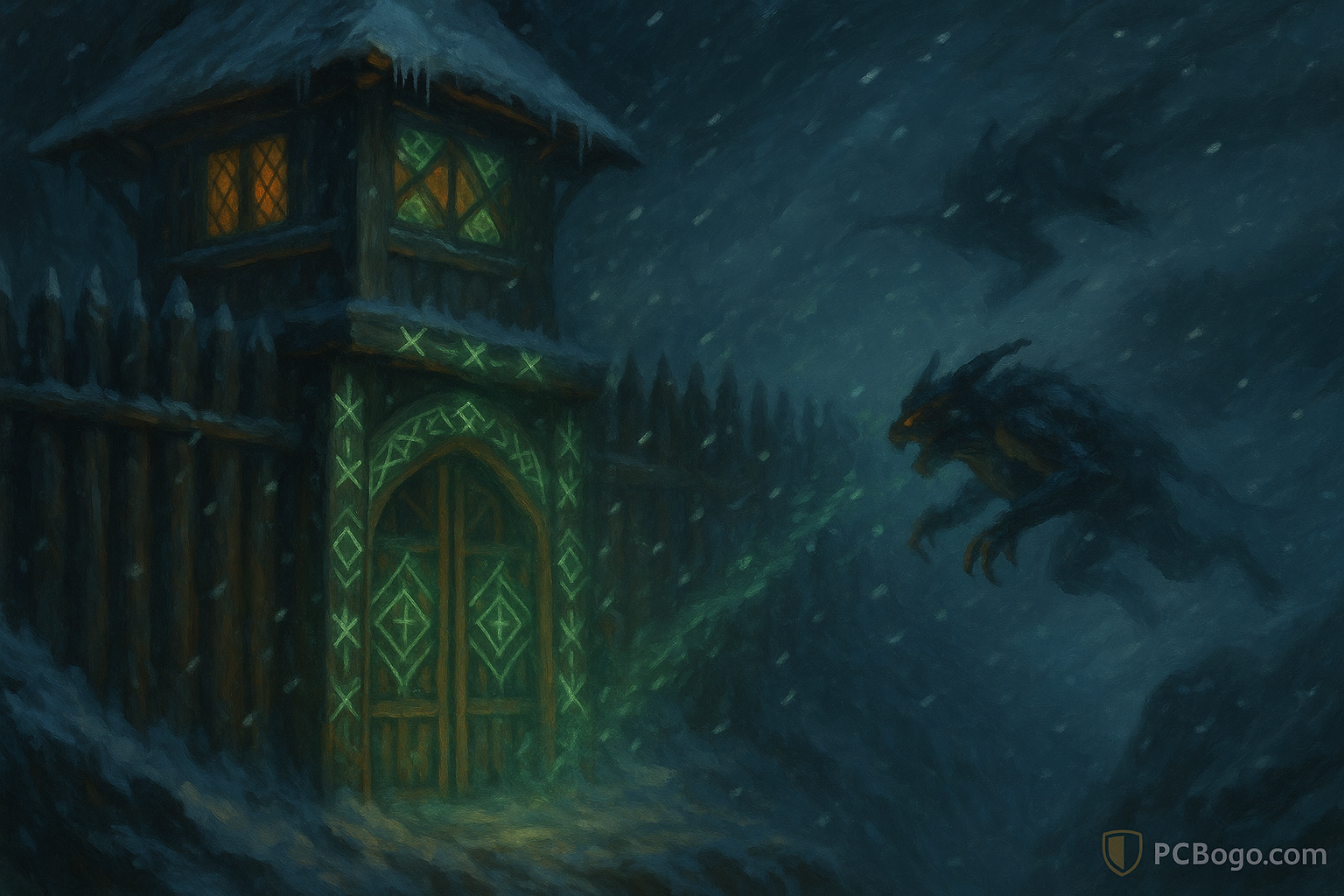

With original epic artwork, we transform legends on paper into storms before your eyes.

This is not an ordinary review site. This is a Sanctuary of Fantasy—built for readers, scholars, and dreamers alike.

Step into this realm where words and visions intertwine, for here you shall witness:

A review can become an epic.

For bilingual readers, a Chinese version of this review is also available.

Fearful Choices, Villagers’ Psyche, and Humanity’s Helplessness in the Night

by Peter V. Brett

Daily Life under Demon Threat: Fragility and Dependence of the Village

In Tibbet’s Brook, ordinary chores are timed against the sky. Morning is for mending fences, trading flour, and ferrying news across lanes; late afternoon is for sweeping porches and checking the lines etched into doors and thresholds. As dusk nears, the village pivots from productivity to preservation. People count tasks not by hours but by how many remain before the first coreling claw might test a flaw in a warded line.

The village’s material world is fragile by design and necessity. Timber walls flex, clay mortar cracks in summer heat, and wagon ruts gather rain that loosens foundations. None of this would matter in a kinder world; here it matters because every gap is an invitation. Daily life revolves around scanning wood grain and stone seams, patching where the eye catches a hairline, and keeping chalk, resin, and spare chisels within reach.

Knowledge is another scaffold the villagers lean on—especially the practical literacy of wards. Adults teach children to recognize forms, to carry a coal for re-inking in a pinch, and to report any smudge without shame. No one expects mastery, but everyone is expected to notice. That noticing—of a nicked lintel, a crooked sigil, a scuffed post—becomes the village’s first defense long before the night’s first shriek.

Scarcity shapes dependence. Messengers bring rumors and remedies, traders carry salt, twine, and stories, and the herb gatherer’s satchel becomes a pharmacy the entire hamlet shares. When a hinge breaks or a plowshare cracks, people barter and borrow because hoarding fails at scale; only coordination keeps the lights and courage up. The jongleur’s songs are not idle diversion but a social glue that steadies hands before sunset.

Under demon threat, contingency is culture. Families rehearse how to cross a lane quickly if a wardline fails, who carries which child, where to regroup, and how to patch under pressure. The rhythm of the day is therefore a quiet choreography of readiness: tasks stacked so that the last moments of light are always free for inspection, corrections, and—when the sun kisses the trees—one more sweep of the eyes along the lines that hold the night at bay.

Dusk dictates the village’s economy as strictly as any market bell. Shopkeepers tally what must be used before night—fresh mortar, lamp oil, chalk—then what can wait until dawn. Children run last-minute errands with twine-wrapped bundles while adults lay out the ward kit near the threshold: cloths, resin, chisels, and a ledger of trouble spots to revisit. When the sky reddens, tasks compress into a single priority: ensuring every line that stands between home and corelings will hold.

Specialists become lifelines. The carpenter who can true a warped lintel on short notice, the miller who keeps grain dry enough to avoid swelling cracks, the herb gatherer who trades poultices for blisters raised by chiseling—their crafts braid into the same rope of survival. Messengers are the village’s moving arteries, exchanging news for shelter and warning which routes suffered failures. Even the jongleur, whose songs seem like luxury, carries mnemonic tales that help the nervous remember stroke order under pressure.

Dependence breeds obligations that feel as binding as law. If a neighbor’s husband is away on caravan, others add her doorway to their inspection circuit; if someone’s chisel hand shakes, a steadier one takes over without remark. Hoarded tools migrate through hands at twilight, marked with a scrap of cloth so they find their way back by morning. No one audits these exchanges; reputation is the spine of the system, and a single lapse can nick that spine in a way no apology can mend.

Education is informal but relentless. Children learn to trace lines in ash before they read their names, to fetch oil before they are trusted with flame, and to narrate out loud what they see as they check a post: crack, smudge, chip, corrected. The point is not perfection but cadence—the practiced path the eyes take along wood and stone. Fear is acknowledged, not shamed; the lesson is to keep fear moving so it does not pool at the feet when the night-sounds start.

Crisis rehearsals confront the chapter’s question: if the wards fail at one house while a cry rises from another, where do you run first? The village’s answer is a ladder of triage—closest breach, most vulnerable occupants, fastest patch—repeated at gatherings until it becomes reflex. It is a hard ethic, but it spares people from inventing morals in the moment. Under demon threat, mercy and math must speak in the same voice, or the night will make the choice for them.

Fear is managed by ritual as much as by tools. Before sunset, families move through the same sequence—wash, eat, check the posts, bank the coals, speak a set of words to steady the hands that will do the last tracing. Ritual makes the unpredictable survivable: when a shriek rakes the dark or a claw taps the siding, the body already knows what to do because it did it in daylight, calmly, step by practiced step.

Dependency carries a price in pride. A household that needs help patching a line must ask before dusk, and asking means admitting weakness that neighbors will remember. Still, in Tibbet’s Brook the ledger cuts both ways: the one who borrows today will be first to answer tomorrow, and reputation rises on how quickly one appears with lamp and chisel when another door calls. The village teaches that strength is measured in reciprocation, not in how long you stand alone.

The economy adjusts to the night’s tax. Lamps burn oil that could have lit workshops longer; chiseling consumes time that could have been spent milling or mending. Some crafts shift to daylight-only schedules, and work that demands deep focus retreats to harvest moons when evenings are brighter. Even joy is budgeted: festivals end early so no one stumbles home in the liminal hour when the first corelings are rumored to test forgotten corners.

Children learn the soundscape of danger. They can tell the difference between wind in the eaves and a scuff against a threshold, between a settling beam and a weight that should not be there. Adults turn this listening into lessons—name the sound, name the fix, name who to fetch—so panic has no empty spaces to grow in. The goal is not to make the young fearless but to teach them where fear belongs: at the edge of attention, not at its center.

All of this dependence aims at one fragile miracle: a night that passes without incident. When dawn comes, the village does not celebrate loudly; it exhales. People check for shattering at the corners, sweep the clutter from porches, and mark the ledger with small notes—smudge corrected, crack sealed, sigil straightened. The work is quiet because quiet is the point: survival without spectacle, a victory counted in chores rather than cheers.

Order is kept by custom more than decree. At dusk the green becomes a council floor: elders compare notes from the day’s rounds, carpenters and millers speak to what wood and grain will tolerate, and families volunteer for corners that need second looks. No one bangs a gavel. The contract is social and enforced by eyes—who showed up, who drifted, who quietly stepped into a gap without being asked.

Economic life knots itself around maintenance chains. A farmer who trades extra pitch for a carpenter’s time, a ferryman who waives a fare if his moorings get inspected, a leatherworker who stitches ward-kits in exchange for help chalking her lintel—these bargains turn scattered crafts into a system. Goods and favors move with a purpose: to keep thresholds square, lines clean, and tools where hands can find them in the half-light.

Seasons change what fragility means. After storms, the village combs the eaves for loosened shingles and hairline leaks that will smudge symbols. In hard winter, blizzard crusts turn paths treacherous and frost heave can twist a door just enough to crack a line; in spring, thaw-swell opens seams that summer heat will widen. The routine adapts—more brushes after rain, more wedges under frames in freeze, more time set aside for inspection when the wind has howled all night.

Signaling is standardized so panic doesn’t have to be invented. A lantern hung high means all clear, a shade half-dropped calls for another set of eyes, a shuttered window with a lamp behind it means bring tools now. Knocks have meanings; so do short tunes the jongleur taught the children. The logic is simple on purpose. In a night when a wrong guess costs more than pride, the village would rather be redundant than clever.

Beneath it all runs the chapter’s hard refrain: dependence is not a failure but a framework. People in Tibbet’s Brook lean because the night leans back; refusing help is just another way to weaken a line. The lesson is lived rather than preached—how quickly you answer a call, how ready you are to ask for hands, how faithfully you return a borrowed chisel by dawn. Survival is the sum of those habits, tallied silently in the ledger of a village that would very much like to see the sun again.

The chapter’s quiet power lies in how it reframes safety as a verb, not a state. Safety is performed: sweeping grit from thresholds so chalk will bind, logging hairline faults before they widen, rehearsing who moves first when a line fails. The village survives not because it is strong in any absolute sense, but because it keeps choosing the work that makes strength appear at dusk and hold until dawn.

Dependence becomes a moral stance rather than an embarrassment. The question embedded in the title—“If it was you”—is not rhetorical; it is the nightly calculus every doorframe demands. Would you knock next door before pride hardens? Would you lift a latch when a neighbor hangs the agreed signal? The chapter argues that the bravest answer is the one that binds hands together, because no ward means anything if the people behind it stand apart.

Fragility, likewise, is reinterpreted as sensitivity. The village’s vulnerability to storms, frost heave, and settling beams teaches a form of attention that is closer to craft than to fear. People learn to read wood and clay, wind and weight, so the world’s small warnings are legible before they become large disasters. That attentiveness is the chapter’s finest tool: a literacy of matter that turns panic into procedure.

Culture carries the load that tools cannot. Songs encode stroke order, market habits ration dusk-hours, and games teach children to name sounds in the dark. The social ledger—who showed up, who noticed, who returned what they borrowed—does the invisible work of holding the lines together. When materials crack and chalk fades, culture supplies the redundancy that keeps the night from finding a way in.

By the last image, the thesis is simple: under demon threat, survival is communal craftsmanship. Every porch-swept, every lintel checked, every call answered is another stitch in a fabric stretched across the village. The chapter closes not with spectacle but with continuity—another morning earned—so that when the story turns toward journeys and larger wars, we understand what is at stake: the ordinary miracles that a warded community makes, one practiced gesture at a time.

Moral Dilemmas: What to Do When Demons Are Outside

The chapter frames an ethical crucible: a knock at night when corelings prowl the lanes. Opening a door means breaking a line—no matter how briefly—and a breach risks more than one household. Yet leaving someone outside to the dark feels like a betrayal of the very idea of a village. The dilemma is not abstract; it is set into every threshold where Defensive Wards meet the human impulse to help.

Communities respond by shaping duty into rules that bite. Most villages teach that you never unbar a warded door after full dark. Aid, if any, is given indirectly: shouting instructions for a safer route, sliding a rope or board through a window slit, or tossing a tool toward the nearest intact circle. These partial measures are not cowardice but a way to balance mercy with containment—help without turning one cry into many.

Hierarchy of claims complicates the night. If the voice outside is a child, an elder, or a messenger whose arrival warns of wider danger, the case for action grows louder—but so does the danger. Some elders argue that precedent matters more than sentiment: break the rule once and every future plea will demand the same exception. Others counter that ethics without room for compassion rots into fear by another name. The dispute is the point; it keeps the rule from calcifying into cruelty.

Individual bravery collides with communal safety. A person who rushes out to haul someone in may be hailed as a hero in stories, but the practical consequence can be a scuffed sigil, a dragged foot across wet chalk, or a claw snagging the lintel as the door swings. The chapter insists on this sober arithmetic: there are acts of courage that protect everyone, and acts of courage that merely look brave while making the village weaker.

The title’s question—“If it was you”—turns the lens inward. Would you want the door opened, risking your neighbors? Would you want it kept barred, trusting that your plight teaches others to move sooner tomorrow? The text refuses a clean answer because the villagers cannot have one. Instead it offers a posture: prepare so well by day that the night forces you to choose as little as possible, and when you must choose, do it for the line that holds the most lives.

Villages reduce midnight tragedy by drafting daytime consent. Families state in advance what they want others to do if they are caught outside after dark—whether to attempt a rescue, to guide them to the nearest circle, or to keep the door barred for the sake of the line. By agreeing before fear arrives, neighbors trade improvisation for clarity. The promise does not erase pain, but it gives the night fewer chances to turn pity into panic.

Threshold ethics are engineered into architecture. Some homes add a shallow porch channel that allows a rope or board to slide across the gap without breaking a ward line; others build a chest by the window slit stocked with oil, chalk, and a hook on a pole. These designs admit that help may be needed while constraining how it can be offered. The house becomes a tutor: it teaches that compassion should travel along grooves already carved in daylight.

Authority matters, but only when it is distributed. Elders and ward-literate artisans set the rulebook, yet the burden of choice is shared at the edges—on stoops and lanes, in the seconds when a voice begs and claws scrape. The chapter underlines this tension: edicts can’t reach every threshold in time, so the culture must train ordinary people to decide well under pressure, to keep their courage inside the chalk.

Alternative aid is cataloged and practiced. People rehearse throwing a sand-weighted line, lowering a shield of planks that can be nudged forward by a trapped person, or rolling a barrel as a moving barrier. A messenger’s cloak might be marked with reflective stitch so a lantern’s flick guides them to safety. None of these tools asks anyone to step over a symbol; each turns ingenuity into distance.

Finally, the community builds moral triage into routine. When cries overlap, priority flows to the closest breach and the most vulnerable voice, then to whoever can reach a safe circle fastest with instructions. By speaking this hierarchy aloud at markets and hearths, the village makes a promise to itself: the decisions that cost sleep will never be improvised alone. If the night forces a choice, at least it will be one the day prepared.

Hard cases expose the limits of tidy rules. A voice begging two doors down is one thing; a cry that sounds like a child at your threshold is another. Villagers train themselves to treat likeness with suspicion—fatigue, wind, and terror can turn any plea into a command to act now. The chapter’s moral pressure point is here: holding your nerve long enough to verify without freezing into indifference.

Verification becomes an ethic of its own. Before nightfall, families agree on call-and-response phrases, tap patterns on wood, and lantern cues that can be exchanged without breaking a line. If the pattern comes back wrong, aid shifts to distance tools—boards, ropes, shouted routes—because the risk profile has changed. The point is not to withhold help but to ensure that compassion lands where it can actually save, not endanger, more lives.

A second edge case is self-inflicted peril. Someone late to return may be drunk, angry, or reckless; another may have ignored market warnings about storm fronts and frost heave. The village resists turning moral judgment into triage, but the tension remains: does culpability reduce claim? The chapter’s answer is pragmatic—priority is set by proximity to breach and vulnerability, not by blame—yet it does not deny the bitterness such rescues leave behind.

Then there are decoys and misunderstandings. Night distorts sound, and fear edits memory; a scrape can masquerade as a claw, a gust as a shout. Villagers keep a ledger of false alarms without scorn, because false alarms train reflexes and reveal weak spots in signaling. The ledger’s purpose is improvement, not indictment: each mistake is a rehearsal that prevents a catastrophe with a higher price tag.

Finally, the aftermath is part of the dilemma. If a door stayed barred and someone was lost, the village meets at first light to walk the route, name every factor, and adjust the protocol. If a door opened and a line smudged, they repair before blame and ask what redundancy was missing. The ethic is circular rather than punitive: decisions at night are judged by what the day is willing to learn from them.

Leadership under night-pressure is a craft of speaking plainly. Elders learn to give orders that are short, testable, and reversible—“Hold the line. Lantern left. Board ready.”—so no one wastes courage decoding poetry. The chapter shows that good command reduces choices rather than inflaming them; it narrows the path until there is only the right next act, and that clarity keeps panic from blooming in the margins.

Stories are the village’s slow ethics engine. Jongleurs turn ugly nights into teachable ballads that encode what worked and what failed: which door should have stayed barred, which signal saved a life, which hesitation cost two. Children sing the refrains while sweeping porches, and adults learn without being accused. Narrative becomes a social tool that sharpens judgment before the next test arrives.

Preparation reframes heroism. Villagers prize the quiet bravery of the person who mends a crack at noon far more than the dramatic sprint at midnight. The text insists that the best rescue is the one never needed: the latch pre-oiled, the lintel squared, the chalk sealed. Even when heroics succeed, they carry a tax—smudged symbols, shaken hands, neighbors who will copy the risk next time. Prevention saves lives; spectacle spends them.

Neighborly trust is audited by behavior, not vows. You are the sort of person who checks the corner you claimed, returns the chisel before dawn, and shows up when the agreed lantern cue glows. In this economy, promises are receipts: they only matter after the act appears. The moral world of the village is practical in this way; it cares less what you swear to do than what you have already done when the night went wrong.

Finally, the chapter argues for humility at the threshold. No one can guarantee the perfect call every time; the night lies and the heart mishears. What can be guaranteed is the discipline to review, to rewrite the protocol, and to forgive the right kinds of mistakes—the ones made while keeping hands inside the chalk. In a warded world, humility is not self-abasement but the maintenance schedule of courage.

The chapter closes by turning policy into posture. The village cannot script every night, but it can decide the kind of people it will be when the pounding starts: careful, coordinated, and unashamed to ask for help. Ethics here is not a courtroom; it is a stance—a readiness to hold two truths at once: that a barred door can be mercy, and that a shouted route can be love.

Responsibility is described as a circle rather than a line. Duties loop from household to lane to green and back again, so that no single threshold bears the full moral weight. Shared drills, shared ledgers, shared signals—these are the ways the burden is distributed. The effect is to de-romanticize sacrifice without belittling it: no one is asked to be a martyr because everyone is asked to be alert.

Memory becomes the village’s conscience. Each night leaves traces—notes in a margin, a new groove in a lintel, a revised refrain in a jongleur’s song—and those traces harden into guidance. People do not argue from abstractions but from last week’s porch, last winter’s storm, the corner where a sigil once smudged. The past is not a chain; it is a toolkit that makes tomorrow’s mercy more precise.

The chapter also repositions fear as a useful instrument. Fear is the metronome that sets the tempo for preparation and keeps hands inside the chalk when voices rise outside. Properly tuned, it sharpens attention without governing it; it warns without ruling. The moral achievement is not fearlessness but stewardship—taking fear in hand and making it serve the line that protects the most lives.

What remains, finally, is a simple imperative: make decisions in daylight that honor the night. Build the channels that allow aid to travel without breaking wards; speak promises aloud so neighbors know what you will do; teach children the difference between noise and need. When the world leaves someone outside, the village answers with a culture that keeps as many as possible inside. That is the ethics the story asks us to admire: courage organized, compassion disciplined, survival shared.

Fear and Cowardice: Humanity Revealed in Extreme Circumstances

Fear in this chapter is not a visitor; it is the climate in which choices are made. The night thickens, the lines glow faintly, and people discover how much of their courage is muscle memory and how much is theater. Cowardice, when it appears, rarely announces itself as such. It borrows the language of prudence—“wait,” “not yet,” “be certain”—until the window for action shrinks to nothing and the silence feels like safety.

The body speaks before the conscience decides. Hands sweat and slip on a latch; breath shortens and makes speech come out as sharp commands when gentleness would work better; eyes over-focus on a single sigil and miss the scuff at the threshold. The text tracks these micro-failures without contempt. They are not sins but physics: the nervous system preparing for flight in a place where flight would erase a line and invite corelings in.

Cowardice hides inside rationalizations that are locally true but globally wrong. A person might refuse to check a corner because “the wind will smear the chalk,” or delay sending a tool because “throwing is noisy.” Each claim has a grain of truth, but the aggregate effect is paralysis. The chapter’s insight is that fear often presents as expertise—precise, plausible, and perfectly calibrated to justify doing nothing.

Courage, by contrast, is repetitive rather than dramatic. It looks like routine: the same calm words, the same careful scan, the same small repair. The brave do not feel less fear; they give it a job. They tell it when to speak—“slow your hand, check the seam, breathe”—and when to be quiet. Heroism here is the discipline that keeps hands inside the chalk and minds inside the plan.

What the night reveals, finally, is not who loves danger but who can love order under pressure. The chapter honors people who choose the unglamorous act that preserves the line for everyone else. They are the ones who accept that fear is a tool with sharp edges: it can cut a rope free or it can cut a circle open. The difference is whether it is held, named, and put to work before the claws arrive.

Fear multiplies in groups, not just in individuals. A murmur by the doorframe becomes a rumor in the lane, and by the time it reaches the green it has turned into certainty that a breach is coming. Cowardice often wears the mask of consensus—“everyone thinks we should wait,” “no one else is opening”—so that responsibility dissolves into the crowd. The chapter shows how the bystander effect thrives where wardlines are strong but moral spines are soft.

Shame is fear’s quieter accomplice. People who froze last week become the loudest advocates of caution this week, drafting their hesitation into village policy. They rewrite their memory of the night—what they heard, what they could have done—until doing nothing feels like wisdom learned the hard way. The text is frank about this self-editing: cowardice survives by turning yesterday’s failure into today’s doctrine.

Language becomes the battlefield where fear tries to win respectability. Phrases like “protect the greater good,” “avoid provoking them,” or “maintain order” can be sincere or evasive depending on who says them and when. Cowardice prefers abstractions because abstractions do not bleed; courage prefers verbs that can be checked—light, look, call, brace. The difference matters at thresholds, where words have to cash out as actions before the chalk dries.

Status complicates what looks like prudence. When a respected artisan or elder hesitates, others pause too, taking their cue from reputation rather than the evidence at hand. The chapter does not vilify deference, but it warns that hierarchy can launder fear into policy. The cure it suggests is procedural: decisions must be short, timed, and reversible, so authority cannot hide behind delay.

At its core, the chapter argues that cowardice is not the absence of fear but the failure to assign fear a task. Left to govern, fear protects pride before people; put to work, it sharpens attention and steadies hands. The test is simple and public: after the night passes, did fear make you clearer or smaller? In Tibbet’s Brook, the villagers learn to grade themselves by that question, because the next shriek will arrive before the debate is settled.

Fear often disguises itself as foresight. People overestimate rare dangers right in front of them while underestimating slow, structural risks—like a lax inspection habit or a missing ledger entry—that make a breach more likely tomorrow. Cowardice adopts the tone of a strategist, forecasting calamities to justify inaction, while true prudence uses the same data to assign small tasks that move the village one notch safer.

Under pressure, minds shrink to tunnels. The villager who can recite stroke orders at noon forgets half of them when the shutters rattle; attention narrows to the brightest sigil and misses the frayed lash on the hinge. The text treats this as a design problem, not a moral failure: training must build wide-angle habits that survive adrenaline—eyes sweep, breath resets, hands verify, then act.

Fear also looks for exits inside other people. Blame becomes a release valve—if someone else is at fault, then my freezing was responsible. Cowardice thrives in that accounting, because absolution costs less than change. The antidote is a culture of specific accountability: what I missed, what I will check next time, who will confirm it. Ownership turns fear into feedback instead of an alibi.

There is a subtler failure: outsourcing courage to symbols. Villagers can treat bright, perfect wards as if they were sentient guardians, and so neglect the human practices that keep them intact. The chapter reminds us that lines are only as alive as the hands that maintain them; courage is not believing harder in chalk but returning, calmly, to the seam that needs one more pass.

Finally, fear can be taught to carry weight instead of casting shadows. When the village asks, “What can fear make us do now?” the answers are measurable: count tools, rehearse signals, rest hands, review the map. Cowardice asks, “What can fear excuse us from?” and the answers are always verbs that vanish—check, call, brace. The difference, in the dark, is the thickness of a line and the breath of a life.

Patience and passivity look alike in the dark, but the village teaches a hard distinction. Patience is time-boxed and procedural—wait for three breaths, sweep the line, verify the cue—while passivity is open-ended waiting dressed as wisdom. The difference is measurable: patience keeps a clock, keeps a checklist, keeps companions; passivity keeps only excuses. The chapter asks readers to hear which voice lives at the threshold.

Roles reveal different fault lines. A meticulous artisan may hide fear inside perfectionism, correcting a sigil past the point of usefulness; a miller may over-weigh risks to justify staying by the grain; a messenger might rush out too fast to prove what they are paid for. Courage answers each in its own key: the artisan accepts “good enough,” the miller steps out when the cue arrives, the messenger waits for the rope without flinching at pride.

Bodies need scripts to resist panic, so the village standardizes counter-habits. Breathe on a count, speak in low phrases that are short and concrete, trace stroke orders with the non-dominant hand during drills to widen the mind’s tunnel. Fear is not banned; it is paired with a task: breathe—look—name—act. People who practice that order become reliable in the seconds when reliability is everything.

The environment conspires with fear and must be decoded. Storms make shutters rattle like claws; a thundercloud can mimic the crack of a Lightning Demon; wind on loose thatch imitates a Field Demon’s scuff. Training catalogs these deceptions so that ears and eyes learn to classify rather than catastrophize. The goal is not bravado but literacy: to read weather, wood, and weight before reading doom.

At dawn, the village tallies not shame but evidence. Who kept the clock, who followed the check, who asked for hands before hands shook—these acts are named and taught forward. Cowardice is corrected without spectacle, and fear is folded back into practice. By refusing to confuse paralysis with prudence, Tibbet’s Brook quietly manufactures a sturdier kind of bravery, the kind that keeps the line thick through the next night.

The chapter’s verdict on fear is not condemnation but cultivation. It treats fear as a raw material that can be smelted into vigilance: the habit of counting breaths before acting, of sweeping the line one last time, of naming what is seen so the hands can follow. Cowardice is what happens when fear is left unworked—when it pools into silence, or gets poured into arguments that never touch the threshold.

Characters are measured by how they budget fear across time. In daylight, the brave invest it in drills and repairs; at dusk, they spend it on clarity—short words, sure motions; at midnight, they save enough to keep the plan intact when the window for action narrows. Cowardice spends everything at once, either in a rush that smudges sigils or in a paralysis that lets the night write the ending.

The community reframes courage as stewardship of attention. It prizes the person who keeps their gaze wide when sound shrinks the world, who can hear the difference between wind and claw, who can admit a mistake at dawn and fold the lesson into the next night’s routine. The opposite of this courage is not terror but pride—the refusal to learn because learning would expose how small one felt when the shutters rattled.

Fear’s final service is moral alignment. Properly guided, it points toward the act that preserves the most lives and the longest future: the line thickened, the tool returned, the signal standardized. It keeps people inside the chalk and outside the stories that make heroes of rashness. The chapter insists that the right kind of bravery leaves behind no spectacle, only a safer morning.

By closing on ordinary gestures—a lantern lowered to signal help received, a ledger updated, a quiet porch swept—the text makes its thesis unmistakable: humanity under pressure is revealed not by grand declarations but by repeatable motions. In Tibbet’s Brook, survival is a practiced craft. Fear has a job. Cowardice, when named, has a cure. And the night, however loud, does not get the last word.

Weight of Responsibility: Who Should Bear the Duty of Protection

Responsibility in the chapter is not a title but a distribution. Protection is treated as a networked duty that lives in routines rather than in a single heroic role. Elders carry judgment, artisans carry precision, parents carry readiness for the young, and neighbors carry the habit of showing up. A village survives when the burden is braided across these strands so no one’s failure becomes everyone’s disaster.

The threshold is the primary jurisdiction. Whoever stands nearest to the line owns the next decision: check the seam, confirm the signal, call for tools. Proximity outranks status because speed outruns ceremony. This design keeps authority portable; a child at a window slit who sees a smudge has the mandate to speak and be heeded, and a passerby who notes a warped lintel is obliged to mark it on the ledger.

Specialists shoulder duties shaped by their crafts. The carpenter guarantees square frames that keep symbols true; the miller guarantees dry stores that won’t swell and crack lines; messengers keep routes mapped and warnings current; the herb gatherer keeps hands able by tending blisters and strains. None of these tasks look like heroism, yet each is a guard post that moves with its keeper from morning to dusk.

Leadership is defined by accountability, not command. Elders set the short, testable protocols and then submit to the same audits as everyone else: did you keep the clock, did you walk your assigned corner, did you return the chisel by dawn. Authority that cannot be inspected is indistinguishable from vanity. The chapter insists that the right to direct comes from being the first to be measured.

Finally, responsibility scales by consent. Households state in daylight what help they accept at night, and the village affirms how far any rescuer may go without breaking a line. These pledges convert sentiment into policy and make bravery legible. In this way the burden of protection is heavy but shareable: each person carries a piece sized to their reach, and the whole adds up to a wall that can hold.

Duty is scheduled before it is felt. Households keep rosters for dusk inspections—the south corner today, the porch seams tomorrow—and redundancy is built in: two sets of eyes per line, two hands per tool. This rotation prevents hero bottlenecks and spreads skill through the population. Responsibility becomes less about temperament and more about timekeeping; if you hold the hour, you hold the task.

Family roles are explicit and practiced. The strongest body does not always carry the heaviest charge; the calmest voice calls signals, the sharpest eye reads lines, the steadiest hand traces. Children are assigned observables—count the lanterns, watch the hinge lash—so their attention has a purpose. By partitioning duties into fitted pieces, the village makes protection teachable instead of innate.

Costs are accounted for like grain. People who take extra corners after a storm are repaid in kind—help at harvest, a repaired shutter, a share of oil. The system converts gratitude into logistics so that duty does not depend on mood. When responsibilities are measurable—so many posts checked, so many tools returned—they can be traded fairly without turning care into charity.

Sanction exists, but it is restorative. A missed corner earns extra training; a forgotten tool earns an early-morning sweep with the person you inconvenienced. The point is not humiliation but reliability: the village treats lapses as correctable gaps in the wall. Public blame would smudge more lines than it straightens, so accountability arrives as companionship and added practice.

Edge cases are pre-assigned. If the carpenter is down with fever, the miller covers lintels; if a messenger is late, the elder on that lane is empowered to revise signals for the night. These contingencies keep duty from collapsing into confusion when one strand snaps. Protection is not a single door held shut; it is a net, and the village knots it anew each dusk.

Responsibility collides with kinship when the voice outside is a relative. The chapter stresses that duty flows by position, not affection: the person at the threshold acts first, even if the cry belongs to someone else’s child and the one listening is a parent. This inversion is deliberate. It keeps love from overrunning the line and turns protection into a craft that anyone present can practice.

Gender and strength are decoupled from obligation. A steady-handed grandmother may trace a flawless patch while two younger neighbors hold lantern and board; a boy at the window slit may be the first reliable witness in a crisis. The village judges roles by reliability under pressure, not by muscle or myth. That standard prevents the burden from defaulting to whoever can lift the heaviest plank.

Conflicts of authority are settled by protocol, not personality. When an elder and a carpenter disagree about whether a lintel will hold, the rulebook decides whose call prevails in that moment. Decisions are short and timed; they can be reversed after the next verification sweep. The point is not to be right forever but to be decisive now, with a path back if new evidence appears.

Myth is harnessed, not obeyed. Stories of The Deliverer can inspire but cannot assign tonight’s chores; hope for rescue does not excuse neglect of the wardline. The chapter is explicit: legends may widen the heart, but only habits thicken the line. A culture that outsources responsibility to prophecy becomes brittle the first time the night is louder than the tale.

Finally, responsibility extends beyond one village’s fence. Messengers carry mutual-aid signals between hamlets, and travelers are briefed on local cues at markets so they know how to ask for help without breaking a line. Protection scales through shared language, not through centralized command. The duty to keep the night out, the chapter argues, is communal first and territorial second.

Protection requires succession, not just presence. Every duty has a second and a third in line so that fatigue, illness, or travel does not leave a gap at the wardline. Succession is practiced aloud—“if I’m not here at dusk, you take the ledger; if you’re delayed, she takes the board”—so authority moves smoothly without drama. Responsibility becomes a relay rather than a spotlight.

Tools carry responsibility tags. The chisel, brush, chalk pouch, and lantern are signed out at dusk and signed back at dawn with quick notes about wear and faults. This small bureaucracy prevents the quiet failure—a dull edge, a cracked lens—that turns into a large breach at midnight. By making custody visible, the village makes duty concrete; the thing in your hand testifies to the promise you made.

Consent defines the reach of rescue. Households declare how far neighbors may act on their behalf if cries come from their door—whether to throw a rope, lower a board, or attempt a guided dash—so hesitation doesn’t come from uncertainty. Consent also protects rescuers from later blame: if all parties agreed in daylight, the night’s choices can be audited against that agreement rather than against hindsight.

Training certifies roles without freezing them. People qualify for specific tasks—signal-calling, lintel inspection, emergency patching—but certificates expire unless renewed by practice. This keeps the roster honest and prevents reputation from standing in for competence. In turn, trainees shadow certified keepers at dusk rounds, learning the rhythm before the first solo decision arrives.

Edges of duty are mapped to the landscape. Corners with bad wind, porches that pool water, gates that stick in frost—these are assigned to more experienced hands, while clean, well-lit runs go to newcomers. The map is updated after each storm, so responsibility shifts with the world rather than pretending the world stands still. In that flexibility lies the strength the night cannot easily pry apart.

The chapter resolves the question of duty by making it measurable, transferable, and humble. Protection is a craft with receipts—tools signed out, corners logged, signals rehearsed—and a craft with heirs: anyone can step into the role because the role lives in procedures, not in personality. Responsibility, finally, is a promise that outlives the night: do the work now so that tomorrow’s choices are fewer and cleaner.

Moral authority flows from service, not speech. The people who decide most at dusk are the ones who showed up most at noon, who mended the hairline crack no one else saw, who returned the chisel with a note about its edge. In this ethic, titles are postscript; reliability is the text. The village trusts hands that have already kept the line thick.

Protection is also an economy of attention. The village invests its sharpest eyes where wind and water conspire, its steadiest hands where chalk often smudges, its calmest voices where panic tends to bloom. Duty, then, is not a burden placed on the willing but a resource aligned with the needed. When attention is budgeted, heroics become rare because emergencies do.

The narrative rejects the fantasy of solitary guardianship. Legends of The Deliverer may kindle resolve, but the chapter insists that what keeps corelings out is a fabric of ordinary obligations—swept thresholds, squared lintels, timed calls—that no single savior can replace. The strongest wall is the one a hundred small promises hold up together.

By dawn, responsibility has a shape you can point to: a ledger updated, a map revised, a porch swept, a tool repaired, a protocol amended. These are the artifacts of a duty carried well. They say, without boasting, that protection in Tibbet’s Brook is not the courage of a moment but the maintenance of a community—work done in daylight so the night has less to decide.

Disputes among Villagers: Tug-of-War Between Self-Preservation and Sacrifice

The chapter captures argument as a nightly craft. People split along lines that sound practical—keep the door barred versus risk a rope toss—but underneath are competing theories of what a village is for. One side defines community as a promise to the inside; the other defines it as a bridge to the outside. Neither claims to be cruel or reckless; each claims to be faithful to the same survival, only measured at a different edge.

Debate has its own choreography on the green. Before dusk, voices rise around barrels and benches: the miller citing the cost of a smudged sigil, the carpenter arguing that a warped lintel is more dangerous than a short rescue, the jongleur reminding everyone what last winter’s hesitation cost. These are not abstractions but audits—each speaker brings evidence from the week’s cracks and patches to argue where courage should stand tonight.

Rhetoric divides along time horizons. The self-preservation camp talks in immediate risks—how many heartbeats it takes to unbar a door, how far a claw can reach through a gap—while the sacrifice camp argues in long returns—how today’s rescue will bind tomorrow’s helpers, how children learn what a village means by what they see at midnight. The argument is a contest between seconds and seasons, each with receipts.

Compromise appears as design rather than persuasion. Instead of “open or close,” some propose “prepare better choices”: a pre-hung board on hinges for guided entry, a rope channel cut into porches, a lantern code that commits neighbors to act in sequence. By changing the tools, the village changes the terms of the quarrel—less about virtue, more about mechanisms that let mercy travel without breaking a line.

The fiercest disputes are about fairness. Who pays when a rescue smudges a stranger’s wards? Who decides whose cry outranks whose? The chapter shows villagers inventing small institutions to cool the fight: a rescue ledger to share costs, a rotating triage caller so authority cannot ossify, and a rule that any exception must be written by dawn or it never happened. Argument, here, is not a storm to be survived but a system to be tended.

Arguments sharpen when stakes are counted in grain, oil, and hours. The self-preservation side points to finite stores—chalk thinned by too many emergency tracings, oil burned on false alarms, sleep lost that dulls hands tomorrow—while the sacrifice side answers with social capital: the goodwill earned by a timely rescue, the future help secured when neighbors know they won’t be abandoned. Each camp claims prudence; they simply budget different currencies.

Motivation is mixed, and the chapter refuses easy halos. Some who argue to keep doors barred are not cowards but caretakers of infants or the elderly; others who press for rescue may be compensating for a past freeze they cannot forgive. Debate, then, is also confession by proxy. People announce what they can live with afterward—smudged sigils and a saved life, or intact lines and a death they could not prevent.

Facts become contested terrain. One side cites how long it takes to unbar a door and how often a sigil smudges under haste; the other presents numbers about successful rope-guides and the low rate of breaches when procedures are followed. The village learns to demand sources: when, where, who, and what was different. Disagreement improves when data must carry names and dates rather than drift as rumor.

Rituals of disagreement keep the quarrel from tearing the fabric. Speakers take turns by lantern order; claims are restated by an opponent before they are answered; and the jongleur summarizes points into a balladly refrain so the memory of the dispute is faithful. The process doesn’t erase heat, but it channels it. Villagers leave with a shared map of the night’s risks even when they still stand on different ledges.

Finally, compromise takes the form of triggers and thresholds. Rescue is greenlit only under agreed signs—a repeated call-and-response, a visible intact circle within rope’s reach, two confirmations from separate windows. If any trigger fails, aid reverts to distance tools. By binding sacrifice to conditions, the village turns virtue into procedure and gives the night fewer chances to convert pity into breach.

Personality colors the fault lines. The cautious frame their stance as stewardship—protecting children, guarding the wardline’s integrity, refusing to let one mistake cascade—while the risk-takers call theirs fidelity to neighbor and future memory. Neither is lying about motive; both are telling the truth their temperaments can carry. The quarrel, then, is not just about tactics but about the kind of people the village is willing to be at midnight.

Evidence is narrated, not just tallied. Someone describes the way chalk clumped on damp wood and how a hasty swipe almost erased a sigil; another recalls a rope-guided entry that saved a panicked trader who would later fund better shutters. These stories function as case law. The chapter shows how precedent shapes instinct: the last near-breach argues for caution, the last clean rescue argues for reach.

Language itself becomes a lever. “Keep the line” can mean bar the door or it can mean keep the circle unbroken while guiding someone in; “help” can be a thrown tool or a hand on a latch. The villagers learn to insist on verbs and conditions: who does what, when, with which tool, under which signal. As definitions sharpen, tempers cool—precision leaves less room for fear to masquerade as reason.

The debate widens to include outsiders. What should be done for travelers who don’t know the local signals or for messengers who arrive bearing warnings that outstrip one village’s capacity? Some argue that generosity must be fenced by procedure, lest pity invite a breach; others suggest building shared codes with neighboring hamlets so aid can cross thresholds without reopening the argument each time.

Finally, the chapter makes room for silence after heat. When voices have thinned and the sky goes bruise-dark, people return to their posts with what consensus they have: a trigger here, a rope there, a signal agreed. Argument is not an enemy of unity but its rehearsal. The village that can dispute cleanly is the village that can act cleanly when the first claw taps the siding.

Power dynamics tilt the debate before words begin. Families with sturdier frames and brighter wards speak more easily for caution; those at the battered edges argue more often for rescue because they remember being outside the circle. The chapter notes how material security hardens opinion, and how the village must correct for this bias if it wants policy made for everyone, not just the best-defended porches.

Debt and gratitude skew the map of courage. A household recently helped in a rope-guided entry tends to vote for reaching out the next time; one that paid dear to replace smudged symbols leans toward barring the door. Neither is wrong, but both are partial. The village’s task is to translate memory into procedure—cost-sharing ledgers, rotating decision roles—so that last night’s luck does not write tonight’s law.

Fear of blame is its own actor at the green. People worry less about being wrong than about being blamed for a wrong that becomes legend. The chapter answers with daylight audits and shared consent forms: if choices are reviewed in public and anchored to pre-agreed triggers, then accountability is collective, and courage can be ordinary again.

Language of honor can inflame or heal. Calling restraint “cowardice” or calling rescue “reckless” turns neighbors into enemies. The village experiments with neutral phrasing—“keep the line,” “extend aid by distance,” “commit to sequence”—to keep dignity intact while decisions stay sharp. Rhetoric, tuned this way, becomes another tool that keeps hands inside the chalk.

The argument narrows, finally, to what is promised at dusk. If the village promises signals, tools, and sequence—and keeps them—the pull between self-preservation and sacrifice slackens. What remains is not a quarrel about character but a choreography of help: who throws the rope, who watches the lintel, who speaks the call. The night may still be loud, but the village is in time.

The chapter resolves argument into architecture. By nightfall, debates become fittings: a rope coiled on the porch rail, a hinged board tested twice, a lantern code pinned by the door. Self-preservation and sacrifice are no longer slogans but settings; the village dials them by condition rather than conviction. What was once a quarrel becomes a set of tools that teach the hands what the mouth could not agree on.

Accountability tames resentment. A rescue ledger spreads the cost of smudged symbols; a rotation for triage calling prevents any one voice from owning the risk; daylight audits separate courage from luck by asking who kept sequence and who kept time. With receipts in place, neighbors stop litigating character and start improving procedure. The village learns that fairness is the grease that keeps the courage engine from seizing.

Ethics filters into language children can carry. “Keep the line” means check the edge before the center; “extend aid by distance” means tools first, bodies last; “commit to sequence” means courage is a team sport. These phrases compress judgment into cues that travel in a shout. When the first scrape comes, the debate is already compressed to verbs that fit between heartbeats.

The story refuses a winner, choosing harmony over victory. The self-preservation camp gains guardrails that keep pity from prying open a circle; the sacrifice camp gains pathways that let mercy travel without breaking Defensive Wards. Both are right in pieces and wrong in isolation. The village’s genius is to weave the pieces into a rhythm that holds when corelings test the siding.

By dawn, the proof is ordinary: a clean porch, an updated map, a note about a hinge lash, a child who can sing the lantern code without missing a beat. The quarrel has not vanished; it has found its place in the maintenance of survival. In Tibbet’s Brook, unity is not the end of argument but its product—courage made procedural, compassion made repeatable, and a warded morning earned again.

Fractures of Communal Trust: Accusation and Alienation

Trust doesn’t shatter in a single night; it thins, strand by strand, until a voice raised at dusk can snap it. The chapter shows how suspicion incubates in small omissions—an unreturned chisel, a corner left unchecked, a lantern cue ignored—and then blooms when fear is loud. Accusation arrives as certainty spoken quickly, and once spoken, it is harder to retract than to repair a smudged ward.

Blame hunts for the simplest target: the person nearest to the latest scare. A miller who delayed a rope toss, a carpenter whose brush ran dry, a neighbor who “heard wrong”—each becomes the story’s hinge for a day. Yet the text reminds us that these incidents are usually symptoms of wider strain: tired hands after storms, tools overdue for care, protocols that were clear to some and murky to others.

Alienation begins with small social edits. A bench shifts to leave a gap when someone sits; a market price firms up where it used to bend; a child is told to sweep a different porch. None of this breaks a wardline, but it erodes the human fabric that keeps hands available when the night claws. The chapter is sharp about this: isolation is a breach in slow motion.

Gossip, here, is a vector. Stories flatten nuance until “hesitation” becomes “cowardice” and “caution” becomes “malice.” The jongleur may sing a refrain that remembers too cleanly, and memory hardens into verdict. The cure the village experiments with is procedural: daylight reviews that keep names attached to facts, and ballads revised to include the messy circumstances that produced the choice.

Finally, trust is shown to be a maintenance task like any other. It is kept by receipts—tools signed back with notes, corners logged with times—and by apologies that are practical: extra rounds walked, extra lines retraced, extra oil shared. The chapter argues that in a warded world, social repair is not sentimental; it is structural reinforcement that keeps fear from turning neighbors into hazards.

Distrust follows a predictable ladder: suspicion, story, verdict, sanction. It starts with a glance held too long at dusk, becomes a tale retold by three doorways, hardens into certainty at the green, and ends as a quiet punishment—a tool not loaned, a signal not answered as fast. The chapter’s point is brutal in its simplicity: by the time blame is formal, the damage to coordination is already done.

Accusation clusters around patterns, not proofs. Trades with visible failure modes—carpenters whose lintels warp, messengers who arrive breathless—draw more heat than faults hidden in storage or ledgers. People confuse salience with guilt: what they can point to, they can punish. The village must relearn that a smudged symbol on a bright porch is not more culpable than a dry brush in a dark shed; it is only easier to see.

Alienation corrodes timing before it fractures policy. A neighbor who felt slighted last week hesitates half a breath before tossing the rope; another delays calling a cue to avoid “owing” a rival. These are not grand betrayals but micro-staggers that widen risk. The chapter measures trust in seconds and syllables: when resentment steals either, the night collects the difference.

Secrecy masquerades as prudence and makes everything worse. Families begin to keep private checklists, alter their porch fittings, or trace idiosyncratic strokes on Defensive Wards so a tool fits their hand but no one else’s. Custom becomes a moat. When standards splinter, help can’t travel; a good rope or brush is stranded two doors away by incompatible habits.

Repair requires institutions, not speeches. The village experiments with a dawn forum where accusations must arrive with times, places, and named witnesses; with a rotating “threshold pair” from unrelated households to co-sign each night’s inspections; with a small oil-and-chalk fund to compensate those whose lines were smudged during sanctioned rescues. Trust, the chapter insists, is not a feeling you wait for. It is infrastructure you build.

Scapegoats emerge where fear needs a face. Outsiders, solitary tradesmen, or families living at the edge of the green are read as risk magnets, and the next close call is hung on them whether or not the facts fit. The chapter is blunt about the economics of blame: it travels to those with the fewest allies and the dimmest porches, because their protests carry the shortest distance.

Trust erodes fastest where tools do not cross thresholds. When a household stops lending a brush or chisel, or refuses to share oil on claim of “short supply,” neighbors read the gesture as moral withdrawal. Protection is a network good; the village learns that private stockpiles produce public deficits—more brittle wardlines elsewhere, more calls unanswered, more reasons to distrust.

Children mirror the fractures adults model. A skipped invitation to sweep a porch becomes a prophecy of future distance; a lantern-code game that excludes one child rehearses a night where that family’s signal will be “missed.” The text insists that social training begins long before dark: every playground slight is a pilot episode for how seriously a cry will be taken at midnight.

Rituals of reintegration matter more than apologies. A family that missed a post can return with visible service—an early-morning sweep, a repaired hinge lash, a fresh tracing on a neighbor’s lintel—and a short statement pinned by the door that logs what was done. These gestures convert remorse into capacity. Trust responds less to contrition than to proof a gap has been closed.

Finally, the chapter shows accusation cooling where language gets precise. “You’re careless” becomes “you left the south corner unchecked at third bell”; “you never help” becomes “we needed two voices for the call-and-response and only one answered.” Specifics make repair assignable. Once faults arrive with time and place, they can leave with a plan.

Trust fractures into micro-tribes before it breaks entirely. Household cliques form around work rhythms—millers backing millers, carpenters taking carpenters’ side—and soon evidence is weighed by allegiance rather than weight. The chapter shows how factions turn ordinary audits into proxy wars: a smudge becomes a pretext, a delay becomes a verdict, and procedure gets outvoted by loyalty.

Markets broadcast hidden rifts. Prices harden for some families and soften for others; help once paid back in favors is now priced in oil and time. When trade stops flexing, resentment crystallizes: “if they won’t bend by day, why should we risk at night?” The village learns to watch the stalls as barometers—when porches look fine but prices go rigid, the wardline is already thin.

Seasonal stress amplifies alienation. After storms and bad harvests, people hoard attention the way they hoard grain, saving patience for their own thresholds. The result is a quiet privatization of courage: doors open slower, ropes are thrown shorter, and the chorus in the call-and-response has fewer voices. Scarcity shrinks the moral circle unless a counter-ritual expands it on purpose.

Memory creates echo chambers. Families replay the same night from their own window and then tell it again at the same bench, to the same listeners, until nuance flattens. The jongleur’s refrain, if left uncorrected, becomes a tunnel through which every future story must pass. The cure is cross-seating: swapping benches, rotating storytellers, and insisting that each account be retold by someone who did not stand there.

Repair requires neutral ground and named mediators. Disputes move to the green with a chalk grid that fixes time and place; a rotating elder pair moderates; and a written summary pins to the notice board for three days so amendments can surface. By giving conflict a public spine—who spoke, what was decided, when it will be reviewed—the village trades rumor for record and makes trust rebuildable.

The chapter closes by turning trust from sentiment into scaffolding. Pledges are written, not implied; signals are diagrammed, not assumed; and apologies are carried by work, not words. When coordination has been frayed by accusation, repair begins with visible routines that make help predictable again—whose lantern answers which call, which porch holds the rope, where the ledger lives at dawn.

Reconciliation is staged, not improvised. A brief amnesty window at first light allows grievances to arrive with facts before they harden into feuds; a rotating neutral pair attests to what happened at each threshold; and the jongleur revises last night’s refrain so memory keeps its edges. These rituals keep shame from curdling into silence and teach the village how to argue without breaking.

Standards travel better than goodwill. Shared templates for porch fittings, latch checks, and call-and-response keep neighbors interoperable even when feelings lag behind. The chapter’s quiet thesis is that compatibility is kindness: a rope that fits any rail, a brush that fits any hand, a signal that any child can carry make accusation less tempting because failure has fewer places to hide.

Leaders earn back credibility by taking the most measurable jobs. Instead of speeches, they walk the early rounds, post the updated map, and sign the receipts for oil and chalk. Authority that touches tools cools tempers; it shows that policy is a posture the hands can hold. When people see decisions arriving with chisel marks and clean seams, suspicion has less air.

By dawn, trust is not a feeling but an artifact: a corrected entry, a standardized bracket, a lantern code sung in the same key on three porches. The community is still human—opinions differ, tempers flare—but the fabric holds because it is stitched with procedures that let courage and care pass between houses. In Tibbet’s Brook, that is how accusation loses its shadow and the night loses a little of its power.

A Boy’s Perspective: Growth from Observation to Questioning

The boy’s gaze is a measuring stick the village did not know it owned. He watches how adults translate fear into routines—how a chisel is signed out, how a lantern answers a call, how a brush lifts at the seam—and begins to sense where habit ends and hesitation begins. Observation is his first apprenticeship: before he can name a ward, he can name the moment a hand trembles.

He notices a mismatch between stories and seams. In the daylight tale, the village is brave and seamless; at dusk, he sees pauses, glances, and the shuffle of feet that contradict the ballad. This gap does not make him cynical; it makes him curious. He starts to collect small contradictions the way others collect tools, laying them out on the porch to see what they can build.

Faces become texts. He learns the elder’s voice when it is certain and when it is buying time; he reads the miller’s caution as care on some nights and as self-protection on others; he hears the jongleur’s refrain as both memory and editing. The boy is not hostile to authority, only allergic to vagueness. His questions grow from wanting the line thicker, not thinner.

Names anchor his learning. He watches Arlen Bales listen longer than others and ask the kind of questions that make adults uneasy—about who decides, how long to wait, what happens if the line fails. He notes how Silvy Bales softens fear with tasks and how Jeph Bales balances caution with pride. The boy’s education is a family of methods, not a list of rules.

By night’s end, observation has ripened into a first, dangerous skill: inference. From a smudge he can guess a hurried hand; from a delay he can guess a doubt; from a careful breath he can guess a choice about to be made. He is still small, but his questions have weight. They do not accuse; they tilt the lantern so everyone can see the same seam.

Observation turns into collection. The boy starts keeping a mental cabinet of details—how long a latch sticks in cold, which seams smudge after rain, which call-and-response gets answered fastest. Facts replace slogans. He learns that fear is not one thing but many small timings, and that knowing those timings is a kind of strength even a child can carry.

Questions sharpen around causes, not culprits. Instead of “who failed,” he asks “what failed first”—the brush that went dry, the lintel that bowed, the cue that came a heartbeat late. Adults hear accusation; he means diagnosis. The chapter lets us feel his frustration when answers arrive as pride or proverb rather than process, and how that gap feeds his resolve to keep asking.

Language becomes a workshop. He tries new words on the world—“sequence,” “verification,” “threshold”—and watches how people react. Some soften, offering steps and measures; others harden, hearing challenge. He learns that a good question is shaped like a tool: specific enough to fit a task, light enough to pass from hand to hand, and strong enough not to bend under worry.

Role models multiply and diverge. He notes how Silvy Bales consoles by assigning tasks, how Jeph Bales translates caution into chores, how Arlen Bales refuses to stop at “because that’s how it’s done.” From each he steals a method: comfort that moves the hands, prudence that moves the feet, curiosity that moves the line. Growing up, for him, is choosing which method to reach for first.

Finally, observation flowers into experiment. He times a door with and without the extra brace, tests how fast a lantern cue travels down the row, and traces a practice seam on scrap wood to see which stroke order survives a jolt. None of this is disobedience; it is apprenticeship by measurement. The boy is still small, but his questions now come with numbers—and numbers, even at midnight, are hard to ignore.

Observation tilts toward agency when the boy discovers leverage. He notices that small prep choices—where a rope is coiled, how a latch is angled, which seam is thickened—change what is possible later under pressure. This is the first quiet revolution: the sense that the night is not only endured but shaped by earlier hands, and that even a child can set those hands to work.

His questions widen from household to village. He wants to know who decides the lantern code, why some porches have better fittings than others, and how a rule written at the green becomes a habit on the farthest door. Institutions come into focus. The boy begins to treat policy as a draft, not a decree, and to test where a careful suggestion can move the line without tearing it.

Curiosity pushes outward to the map beyond the hedges. He asks what signals are used in Riverbridge, what stories are told in Angiers, and whether The Free Cities practice the same call-and-response. Legends of The Deliverer interest him less as destiny than as design: what did those heroes do at dusk that an ordinary village could borrow tonight? The world, to him, is a catalog of methods.

Fear becomes data, not a taboo. He notes which sounds of corelings always precede a scratch, which gusts of wind mimic claws, and which kinds of silence mean the lane is clear. He does not pretend not to be afraid; instead, he learns to name fear’s components until there is less left over to rule him. The chapter shows him changing the question from “am I brave?” to “am I prepared?”

Finally, the boy’s ethics take form. He struggles to balance the duty to keep the line with the duty to answer a cry. His questions seek criteria, not permission: what thresholds trigger aid, what receipts make risk fair, what routines turn mercy into something the whole village can carry. Skepticism, here, is not rebellion; it is care stubborn enough to ask for a better way.

The hinge from watching to speaking is social, not technical. The boy discovers that questions asked in private are tolerated, but questions asked on the green change the room—adults glance at one another, stories harden, and procedures suddenly need defending. This teaches him a second craft: timing inquiry so it opens doors rather than slamming them, and choosing audiences that can turn an answer into action.

He learns to prototype courage at a child’s scale. With two friends he rehearses call-and-response, invents a porch game that mirrors the lantern code, and practices rope throws with a rail no higher than a waist. Play becomes policy in miniature. By shrinking the stakes, he can test what order of steps works best and carry the proof to adults who only trust what hands have tried.

Authority becomes a study, not an obstacle. He maps who owns which decisions—who keeps the ledger at dawn, who revises the sequence after a storm, who signs out brushes when supplies run thin. The boy stops treating “no” as a wall and starts hearing it as a location in the village’s circuitry. Once he knows where a choice lives, he can bring the right kind of question to the right door.

Fear’s vocabulary expands alongside his own. He separates jump-start panic from slow-burn dread, learns which one needs a breath and which one needs a task, and notices how a clear verb—check, signal, brace—can steady a crowd faster than comfort can. The lesson is not that fear is shameful, but that fear responds to structure; a good sentence can be as protective as a thick seam.

Finally, he begins to sense a different horizon for skill: beyond copying adults lies invention. If a seam smudges in the same place each rain, why not alter the stroke order; if a latch sticks every frost, why not change the angle; if a cry is lost in wind, why not add a second cue. The boy’s questions are not petitions for permission but sketches of improvement, the first drafts of a future in which lines hold because someone dared to redraw them.

The night gives the boy a grammar for courage. He learns that readiness is a sentence with verbs—check, signal, brace, guide—and that each verb belongs to a beat. When adults skip a beat, he can name which verb fell out. This fluency is not bravado; it is a map he can carry when fear scrambles thought.

His questions gain an ethic of scope. He begins to judge ideas by how many neighbors they protect, not by how tidy they sound. A hinge fix that helps three porches outranks a clever trick for one, and a lantern code a child can remember outranks a complex signal that flatters the clever. The boy’s measure of wisdom becomes portability: what travels fastest under pressure is what is truest.

Imagination turns practical. He sketches small changes—thickening the seam where rain runs, angling latches that freeze, pre-coiling rope on the rail that faces prevailing wind—and watches adults test them. When something works, he writes it down and watches it become routine. Innovation, he discovers, is not a miracle but a series of survivable edits to the ordinary.

Heroes shift from statues to templates. The Deliverer becomes less a savior than a syllabus: a way to think about dusk, a habit of turning awe into steps. He studies Arlen Bales for this very reason—not to worship boldness, but to copy the discipline of asking what comes next. Courage, in this understanding, is not the absence of fear but the presence of sequence.

By dawn, the boy has crossed a quiet threshold. He is still small, still listening, but his seeing has weight: he can translate a smudge into a question, a delay into a plan, a fear into a tool. The chapter leaves him poised where observation becomes contribution, where a child’s careful words can thicken a line. The village does not yet call this Wardsight, but that is what it looks like when it begins.

Shadows of the Future: Psychological Foreshadowing of Rebellion

Rebellion begins as a private measurement of limits. The boy watches how adults trust Defensive Wards as ceilings rather than tools, and he feels the gap between survival and sovereignty. Each pause at the latch, each story that ends with “that’s the way it is,” plants a counter-story: perhaps the line can move. The seed of defiance is not fury but curiosity about boundaries that look natural only because they are old.

Restlessness gathers around names and places. Arlen Bales listens longer than others and asks why a circle may not be redrawn; stories of The Free Cities and Angiers hint that customs vary, so perhaps necessity is local, not absolute. Even the legend of The Deliverer shifts from prophecy to possibility: if deliverance was ever engineered, it can be replicated. The boy files these hints as blueprints, not miracles.

Fear becomes a teacher rather than a jailer. He catalogs which sounds of corelings precede which strikes and learns that terror has patterns. The moment fear becomes legible, it loses a little of its law. Rebellion here is epistemic: to name is to loosen. When the night is mapped in beats instead of mysteries, the mind begins to ask what beat could be added next.

Authority exposes its seams. He notes when elders defend procedure with reasons and when they defend it with reputation; when the jongleur edits memory to fit a refrain; when a ledger entry closes a question faster than an argument can. These observations do not breed contempt; they breed criteria. The boy begins to believe that better reasons can one day overrule older habits.

Finally, hope applies for a job. He imagines small edits—a thicker seam where rain runs, a second cue when wind eats the first, a hinge angle that does not freeze—and sees how such edits, multiplied, could change the night’s contract. Rebellion is foreshadowed not by speeches but by prototypes: modest changes that suggest a future in which the village chooses more than it fears.

Defiance first practices as doubt. The boy registers how often “that’s the rule” arrives without a reason, and how often reasons arrive that don’t fit the facts. Each mismatch is a rehearsal for saying no—not to people, but to inevitability. Rebellion germinates in the space between an answer and an explanation.

Foreshadowing hides in logistics. He notices that the village’s strongest habits cluster around convenience rather than effectiveness—ropes coiled where they look tidy, not where wind helps; lantern codes optimized for memory, not for noise. The thought that order might be redesigned, not merely obeyed, is the chapter’s quiet spark.

Comparison is the solvent of awe. Stories from Riverbridge and Angiers differ at the edges—another sequence here, a different hinge there—and the variations loosen the grip of “only this way.” If practices can vary, outcomes may depend on design, not fate. The Deliverer becomes a hypothesis: perhaps deliverance scales from method, not miracle.

Fear itself contains a permission slip. Once the boy can predict which sounds of corelings announce which strikes, he intuits that pattern can be met with counter-pattern. Where there is sequence, there can be counter-sequence. The mind, now counting beats, begins to draft responses that don’t exist yet.

The moral horizon tilts forward. He starts to test ideas by their future users—children, the tired, the scared—not by their inventors. Anything that lowers the skill floor feels like a step toward rebellion, because it shifts power from talent to procedure. The line will not move with speeches; it will move when more hands can move it.

Rebellion gathers where safety scrapes dignity. The boy clocks how often survival requires a bowed head—voices lowered at the green, ideas trimmed to fit the frame—and senses a tax being paid in self-respect. Living behind symbols meant to protect begins to feel like living under them. The crack that opens is not hatred of elders, but the conviction that safety and stature should not be enemies.

Ritual fatigue becomes appetite for design. He can recite the porch sequence blindfolded, but repetition without refinement tastes stale. The more the village treats routine as an end, the more he suspects routine is only a scaffold. The desire that stirs is not to smash what works, but to keep building until what works also breathes.

Opposition shapes the contour of his will. A respected elder’s gentle “not yet,” a neighbor’s sharp “who are you to ask,” the jongleur’s neat refrain that erases mess—each teaches him what kind of resistance he wants to avoid becoming: petulant, personal, performative. His imagined defiance aims for another register—procedural, transferable, hard to dismiss because it helps.

Symbols tilt in meaning. The wardline that once marked safety begins to read as a horizon, and horizons exist to be approached. He notices how language can either freeze or free: call a line a boundary and feet stop; call it a prototype and hands arrive. Even the fear-sounds of corelings begin to feel like cues; where others hear an ending, he hears a count-in.

Quiet commitments accumulate. He keeps a pocket tally of small improvements and who listens; he sketches variant lantern phrases that a child could sing; he notes which households answer faster when a messenger is in the lane. None of this is rebellion yet. But it is the grammar of a future argument, one that will ask the village to choose growth without abandoning guard.

Foreshadowing speaks in micro-choices. The boy begins to stand where he can see two porches at once, pockets chalk shavings without asking, and listens for the second beat after a call instead of the first. None of this breaks a rule; all of it rehearses a different posture—eyes on the edges, hands ready to edit, attention tuned to the part of the night no one is watching.