Sanctuary of Fantasy: About

Here, a review is not a handful of words—it is a journey across worlds.

With tens of thousands of words, we unravel the souls of characters;

With original epic artwork, we transform legends on paper into storms before your eyes.

This is not an ordinary review site. This is a Sanctuary of Fantasy—built for readers, scholars, and dreamers alike.

Step into this realm where words and visions intertwine, for here you shall witness:

A review can become an epic.

For bilingual readers, a Chinese version of this review is also available.

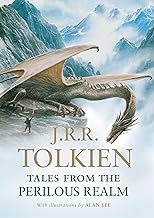

Tales from the Perilous Realm – Reviews & Guide

A complete reading and analysis guide to Tolkien’s lesser-known masterpieces

Beyond Middle-earth: A Deep Literary Critique of Tales from the Perilous Realm

Exploring Symbolism, Style, and Subcreation in Tolkien’s Shorter Works

by J.R.R. Tolkien

J.R.R. Tolkien is best known for The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion, epic works that constructed the vast, mythopoeic landscape of Middle-earth. However, in Tales from the Perilous Realm, readers are invited to witness a different facet of Tolkien’s genius—one that is intimate, playful, philosophical, and profoundly rooted in his lifelong reflections on language, storytelling, and the human spirit.

Introduction – The Perilous Realm Revisited

J.R.R. Tolkien’s Tales from the Perilous Realm stands as a luminous gateway into the lesser-known but deeply significant corners of his legendarium. While most readers associate Tolkien with the epic grandeur of The Lord of the Rings and the mythic vastness of The Silmarillion, this collection offers a more intimate, reflective, and playful side of the author’s creative mind. Here, in this perilous yet wondrous realm of short fiction, Tolkien explores the essence of fairy-stories, the purpose of art, the burden and beauty of mortality, and the redemptive power of imagination.

Comprising five main works—Roverandom, Farmer Giles of Ham, The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, Leaf by Niggle, and Smith of Wootton Major—this collection showcases the breadth of Tolkien’s literary range. Each story, though stylistically distinct, shares a common thematic concern: the intersection of the mundane and the magical, the everyday world touched by the marvelous. These tales do not merely serve as pleasant diversions but as deliberate reflections on the nature of myth, storytelling, and the spiritual longing embedded within modern life.

Roverandom offers a whimsical yet poignant meditation on displacement and transformation, born from a story Tolkien created to comfort his son after the loss of a toy. Farmer Giles of Ham delivers a tongue-in-cheek subversion of heroic conventions, portraying an unlikely hero navigating a comic medieval landscape. The Adventures of Tom Bombadil delves into poetry and mystery, bridging the lyrical and the arcane within the borders of Middle-earth. Leaf by Niggle, perhaps the most personal of the five, allegorizes the artist’s struggle to reconcile duty and creative vision. Smith of Wootton Major, in turn, presents a quiet parable about grace, craft, and the fleeting nature of enchantment.

Together, these stories articulate Tolkien’s vision of what he termed the Perilous Realm—a literary space where danger and beauty intertwine, where readers may be “taken out of this world” not to escape reality, but to better understand it. In his seminal essay On Fairy-Stories, Tolkien described such tales as offering “consolation,” “escape,” and “recovery.” Each of the works in this collection manifests those very principles: consolation in loss, escape into wonder, recovery of meaning and hope.

Moreover, Tales from the Perilous Realm serves as a map to Tolkien’s philosophical and theological landscape. Themes such as sub-creation, stewardship, humility, and grace ripple through these stories in subtle but unmistakable ways. For those already familiar with his epic works, this collection offers a complementary lens through which to appreciate the deeper roots of Tolkien’s mythology. For new readers, it stands as an accessible, enchanting introduction to his world.

Ultimately, this is not merely a collection of tales but a testament to Tolkien’s lifelong conviction that fantasy is not the opposite of reality, but its luminous mirror. These tales remind us that behind every ordinary moment may lie a glimpse of wonder, that art can elevate the soul, and that even the smallest story may carry eternal truths.

The Nature of Faërie: Tolkien’s Theory and Practice of Fantasy

J.R.R. Tolkien’s Tales from the Perilous Realm is more than a collection of short fantasy stories—it is also a demonstration of his enduring belief in the power of Faërie, or what he termed the realm of enchantment. In these tales, Tolkien does not merely tell stories for entertainment; rather, he presents a coherent artistic vision rooted in his academic understanding of myth, language, and human creativity. To fully appreciate these stories, one must engage with Tolkien’s theory of fantasy, most notably articulated in his seminal essay “On Fairy-Stories.”

Tolkien defines Faërie not as a mere escapist dream, but as a world of Secondary Creation—a coherent imaginative realm with internal consistency, beauty, and moral truth. He emphasizes that true fantasy offers recovery, escape, and consolation—functions he considers essential for the human spirit. “Recovery” allows us to see the familiar anew; “escape” provides freedom from the drudgery of the mundane world; and “consolation” culminates in the eucatastrophe—a sudden, joyous turn that affirms hope.

These principles are not just theoretical; they are embodied in Tales from the Perilous Realm. In “Leaf by Niggle,” the allegory of a struggling artist touches on divine grace and the value of imperfect human effort. “Smith of Wootton Major” explores the intersection between mortal life and Faërie, where wonder is both elusive and transformative. Even lighter works like “Farmer Giles of Ham” and “The Adventures of Tom Bombadil” reflect Tolkien’s linguistic playfulness and his affection for pre-modern sensibilities.

What makes these tales uniquely powerful is their tone of quiet reverence. Tolkien’s fantasy is never loud or overbearing; it is meditative, deeply rooted in an ethical vision of the world. He resists cynicism and moral relativism, choosing instead to affirm the possibility of goodness, sacrifice, and the unseen spiritual dimensions of reality.

In an age where fantasy is often commodified or reduced to spectacle, Tolkien’s approach remains revolutionary. He reminds us that fantasy, when done with artistic integrity and moral seriousness, can reach profound truths about our condition. Tales from the Perilous Realm is not a retreat from reality, but a journey deeper into its spiritual and imaginative dimensions—an invitation to perceive the eternal through the lens of the mythical.

Absurdity and Anti-Heroism: The Satirical Power of Farmer Giles of Ham

Among the stories in Tales from the Perilous Realm, Farmer Giles of Ham stands apart as a whimsical yet sharply satirical tale that challenges traditional heroic ideals through absurdity and anti-heroism. At first glance, it may seem like a light-hearted fable, but Tolkien wields humor and irony to subvert conventional medieval tropes, creating a story rich in meaning and critique.

Unlike Tolkien's more solemn works, this story features a protagonist who is neither noble-born nor especially brave. Farmer Giles is a plump, reluctant hero whose adventures begin not out of courage or destiny, but by accident. He becomes a local legend after shooting a wandering giant with his blunderbuss—not out of valor, but by sheer luck and self-interest. In this way, Tolkien introduces the concept of the anti-hero: a central figure who lacks the traditional attributes of a hero but still stumbles into greatness.

The setting of Farmer Giles of Ham is intentionally anachronistic, blending elements of medieval England with fairy-tale absurdities. The language is playful and archaic, reminiscent of faux-historical chronicles. Tolkien uses this style to mock the grandeur often found in epic literature. Kings are petty and cowardly, dragons are bureaucratic, and heroic weapons are more a matter of legend than utility. The talking sword Caudimordax, for instance, is more of a humorous artifact than a symbol of power.

At its heart, the tale is a satire of power structures and the myths that sustain them. Farmer Giles’s rise to prominence mocks the idea that only the noble and valiant are destined for greatness. Instead, it is luck, wit, and local reputation that elevate him. This reversal serves as Tolkien’s critique of both political authority and the literary idealization of the hero.

Yet despite its comic tone, Farmer Giles of Ham shares deeper thematic roots with Tolkien’s broader legendarium. It questions the nature of heroism, the legitimacy of rulers, and the role of myth in shaping perception. In doing so, it reveals Tolkien’s ability to blend humor with profound commentary—proving that fantasy, even in its most playful forms, can be a powerful vehicle for truth.

Rover’s Journey: The Deep Structure of Children’s Fantasy

J.R.R. Tolkien’s Roverandom, the whimsical yet philosophically resonant tale of a little dog transformed into a toy and cast upon a cosmic journey, is far more than a children’s bedtime story. Hidden beneath its light tone and fantastical surface lies a profound exploration of the narrative architecture of children’s fantasy—an architecture that Tolkien both inherited and reshaped. Roverandom is not simply a story about magic, but about the child’s confrontation with loss, exile, growth, and ultimately, return.

The story originated in personal sorrow: Tolkien composed Roverandom in 1925 to console his son Michael, who had lost a favorite toy dog on a seaside holiday. Yet the tale transcends its origins, becoming a meditation on displacement and recovery. The protagonist, Rover, is changed by a wizard’s curse into a toy and embarks on a surreal odyssey that includes visits to the Moon, the deep sea, and encounters with dragons, merfolk, and other fantastic beings. Each phase of Rover’s journey follows a classic mythological arc—a descent into the unknown, trials that test character, and a return transformed.

Tolkien’s mastery is evident in how he maps this structure onto a child’s emotional landscape. The sense of being lost or forgotten, the fear of not being able to return home, the bewilderment of change—these are experiences central to both the child’s imagination and real-life development. Rover’s transformation is symbolic: he becomes small, helpless, and disconnected, only to gradually grow into wisdom and self-awareness. This journey echoes what Tolkien described in his essay “On Fairy-Stories” as the essential elements of fantasy: Recovery, Escape, and Consolation.

Roverandom also illustrates Tolkien’s distinct view of children’s literature. Unlike many Victorian or Edwardian fantasies that either patronize or over-moralize, Tolkien respects the imaginative intellect of the child. His storytelling does not preach but evokes wonder and invites contemplation. The whimsical tone never undermines the emotional depth; instead, it enhances the narrative’s impact by luring readers into a world where the fantastic reveals deep emotional truths.

Furthermore, Roverandom serves as an early example of Tolkien's evolving legendarium. The Moon, for instance, is not merely a backdrop but a fully realized world with its own mythology, customs, and characters—foreshadowing the meticulous world-building that would characterize Middle-earth. In this sense, Roverandom is both a standalone children’s tale and a narrative echo of Tolkien’s broader mythopoeic vision.

Ultimately, Roverandom endures not simply because it is charming or imaginative, but because it captures the deep emotional rhythms of a child’s inner life. It transforms grief into adventure, fear into curiosity, and alienation into understanding. In doing so, it reaffirms Tolkien’s belief that fantasy, far from being escapism, is a path to truth.

Songs and Riddles: The Poetic Narrative of Tom Bombadil

Among the tales included in Tales from the Perilous Realm, The Adventures of Tom Bombadil stands out not only for its whimsical tone and playful spirit, but also for its sophisticated use of poetic narrative. This collection of poems offers a window into the heart of Tolkien’s literary artistry—where language, myth, rhythm, and subcreation meet to form a unique expression of faërie.

Tom Bombadil is one of Tolkien’s most enigmatic and captivating figures. Though he plays only a minor role in The Lord of the Rings, he has inspired much speculation due to his seeming timelessness, his immunity to the Ring’s power, and his joyful, song-filled existence. In The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, Tolkien explores this character further—not through prose, but through poetry, allowing the narrative itself to adopt the fluid and elusive qualities of its subject.

The collection is structured around song and rhyme, presenting readers with a series of lyrical tales that, while simple on the surface, are layered with deep resonance and symbolic complexity. The rhythm and meter serve not only aesthetic purposes but also reinforce thematic motifs of mystery, nature, identity, and the boundaries of the known and the unknown. Tolkien’s use of repetition, internal rhyme, and alliteration imbues the poems with a musicality that echoes oral tradition—reminding us that Middle-earth is as much heard as it is seen.

Moreover, The Adventures of Tom Bombadil embodies Tolkien’s theory of “sub-creation”—the idea that fantasy is a secondary world with its own logic and consistency, brought forth through imaginative craftsmanship. By presenting Bombadil in verse, Tolkien underscores the harmony between form and content: a character who defies explanation is best rendered through a medium that resists linear narrative and embraces ambiguity.

The poems also function as riddles—not only in the literal sense (some are framed as riddling games), but metaphorically, inviting readers to engage in interpretive play. Bombadil’s identity, his origins, and his place in the world are never clearly defined; instead, Tolkien offers glimpses, suggestions, and songs that circle around meaning without ever pinning it down. This aligns with the very nature of faërie, which thrives on wonder, uncertainty, and the glimmer of something just out of reach.

In this way, The Adventures of Tom Bombadil is not merely a lighthearted interlude or an eccentric aside—it is a poetic meditation on the power of language, the nature of myth, and the joy of mystery. Through songs and riddles, Tolkien invites us to listen rather than analyze, to feel rather than dissect, and ultimately, to embrace the enchantment that lies at the heart of fantasy.

Niggle’s Redemption: Art, Faith, and Tolkien’s Allegorical Vision

Among the many gems in Tales from the Perilous Realm, “Leaf by Niggle” stands out as a deeply personal and spiritual tale, often read as an allegory of Tolkien’s own anxieties and hopes as both an artist and a Christian. Though Tolkien was famously cautious about allegory, “Leaf by Niggle” remains one of the few stories he acknowledged to be consciously allegorical. In it, he blends themes of artistic creation, duty, suffering, and salvation into a compact, luminous parable about the soul’s journey through life, death, and beyond.

Niggle, a minor artist obsessed with painting a single tree leaf that gradually expands into an entire tree and forest, embodies the struggle of any creative individual caught between inner visions and external obligations. His obsession with detail and ideal beauty reflects Tolkien’s own perfectionism, particularly evident in his lifelong labor over The Silmarillion. Yet Niggle is constantly interrupted by his sickly neighbor Parish and the demands of daily life, echoing the tension between artistic solitude and moral responsibility.

The story takes a sharp turn when Niggle is unexpectedly summoned on a “journey”—an allegorical stand-in for death. At first, this journey leads to a kind of purgatorial workhouse, where Niggle is required to perform menial tasks, a symbolic purging of selfishness and artistic pride. But eventually, he is released into a heavenly realm where his painting has come to life: the tree he envisioned now exists in full glory, not as an incomplete canvas, but as a real and living world. It is in this place, shaped by his art and purified intentions, that Niggle finds joy and peace.

“Leaf by Niggle” is Tolkien’s profound meditation on the relationship between art and salvation. It suggests that even the most seemingly insignificant artistic act—like painting a single leaf—has eternal value when created in humility and faith. Art, in this vision, is not only an individual pursuit but a means of participating in divine creation. Niggle’s redemption does not come through acclaim or fame, but through compassion, endurance, and spiritual readiness.

The story also subtly critiques the modern world’s utilitarianism. Niggle’s artistry is repeatedly devalued by the practical-minded society around him, a reflection of Tolkien’s own frustration with a culture that marginalizes fantasy and imagination. In the end, however, it is Niggle’s creative vision—what seemed useless and unproductive—that endures beyond death and becomes part of paradise itself.

In this brief but luminous tale, Tolkien articulates a uniquely Christian artistic philosophy: that true art is not measured by worldly success, but by its alignment with goodness, beauty, and eternal truth. “Leaf by Niggle” remains a quiet masterpiece, a gentle testament to the redemptive power of art shaped by love, sacrifice, and faith.

Forging the Soul: The Metaphor of Maturation in Smith of Wootton Major

Among the tales in Tales from the Perilous Realm, Smith of Wootton Major stands out as a quiet masterpiece—a subtle and luminous meditation on imagination, maturity, and the cost of bearing a gift. Written late in Tolkien’s career, this short story functions not only as a children’s fairy tale but also as a deeply personal allegory of creative and spiritual development. Through the life of the titular Smith, Tolkien explores what it means to live with wonder, to confront the loss of innocence, and to ultimately pass on one’s gift in humility.

The central metaphor of Smith of Wootton Major is the star—the fay star that accidentally enters the boy's mouth in the Great Cake and becomes embedded in his forehead. This star is more than a magical trinket; it symbolizes a profound, transformative power: the capacity to perceive Faërie, the magical otherworld that lies beyond the mundane. With this gift, Smith gains access to realms of beauty, peril, and truth—experiences that shape his soul across years of solitary wandering.

Tolkien uses Smith’s journey into Faërie to dramatize the path of maturation, especially in the creative or spiritual sense. Faërie here is not just a fantastical setting, but a landscape of growth, sacrifice, and transience. Smith experiences its wonders but also comes to realize that the gift is not his to keep forever. The act of giving up the star—freely and without resentment—becomes the climactic moral gesture of the story, signifying not a loss but a transcendence. In relinquishing the gift, Smith affirms a deeper kind of wisdom: that the role of the artist, the visionary, or the dreamer is ultimately to steward wonder and then to let go.

Moreover, Tolkien subtly contrasts Smith’s humility with the petty ambition of Nokes, the cook who cares only for appearances. Nokes’ failure to understand the cake’s true meaning or to recognize Faërie when it stands before him functions as a warning against superficiality and ego. The tale thus becomes a meditation not only on personal maturation but also on the social responsibility of imagination—how the magical must be tended with reverence, not exploited for pride or comfort.

In Smith’s farewell to Faërie, Tolkien’s own farewell to the mythopoeic imagination can be glimpsed. There is sadness, yes, but also grace in the letting go. The tale encourages readers not to cling to wonder selfishly but to allow it to flow onward, nourishing others. In doing so, Tolkien affirms his own role as a sub-creator—one who does not hoard Faërie, but shares it, and steps aside when the time comes.

Tolkien Beyond Middle-earth: Modernity’s Distance from Enchantment

J.R.R. Tolkien is most renowned for his Middle-earth legendarium, yet Tales from the Perilous Realm offers readers a glimpse into another dimension of his creative universe—one that challenges our modern notions of fantasy, belief, and imagination. These tales, though smaller in scale than The Lord of the Rings, function as miniature portals to realms where the boundary between reality and wonder is blurred. In this way, Tolkien draws attention to what modernity has lost: a deep sense of enchantment.

The modern world, with its scientific rationalism and secular frameworks, often regards enchantment as mere escapism. Yet Tolkien resisted such a reductionist view. For him, fantasy was not about denial of reality but a reframing of it—what he termed “recovery,” the ability to see the familiar anew. The stories in Tales from the Perilous Realm each enact this recovery in distinct ways: through the whimsical resilience of Tom Bombadil, the tragic beauty of Niggle’s journey, or the haunting wisdom of Smith of Wootton Major. These are not just children’s tales—they are acts of imaginative restoration.

Tolkien’s tales stand in quiet defiance of a world increasingly disenchanted. They do not propose a return to a pre-modern world, but rather a spiritual reawakening within the modern one. They call upon readers to embrace humility, wonder, and faith—not in dogma, but in the power of stories to reshape hearts. The perilous realm, then, is not a distant country but a nearby path obscured by distraction and cynicism.

In stepping beyond Middle-earth, Tolkien invites us to reflect not just on other worlds, but on our own. What is the cost of modernity’s skepticism? What has been lost in our pursuit of progress? And most importantly, how might the perilous realm still be accessed—through poetry, myth, and the quiet courage to believe in more than what can be measured? Through these seemingly modest tales, Tolkien reclaims enchantment not as nostalgia, but as necessity.

The Significance of the Perilous Realm: Positioning the Short Stories in Tolkien’s Canon

In the towering legacy of J.R.R. Tolkien, works like The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings dominate popular imagination, with The Silmarillion forming the mythic bedrock of Middle-earth. Yet Tales from the Perilous Realm presents a different, more intimate side of Tolkien’s storytelling—a collection of short works that occupy a unique place within his legendarium. While these tales may lack the grand narrative scope of his epics, they possess a quiet intensity and philosophical depth that enrich our understanding of Tolkien’s vision.

The “Perilous Realm” is not merely a collection of fantastical places, but a conceptual space where the ordinary intersects with the extraordinary, where language, myth, and morality are tested and transformed. These stories—Farmer Giles of Ham, Smith of Wootton Major, Leaf by Niggle, and The Adventures of Tom Bombadil—form a constellation of miniature myths that resonate with the central themes of Tolkien’s larger works: the sacredness of subcreation, the redemptive power of beauty, and the spiritual dignity of the humble.

Crucially, these short stories allow Tolkien to explore ideas he could not easily integrate into his larger Middle-earth narratives. In Leaf by Niggle, for instance, he meditates on the role of the artist in a world of utility and obligation. In Smith of Wootton Major, the encounter with Faërie becomes a metaphor for personal growth, grief, and the fleeting nature of joy. Farmer Giles of Ham subverts the heroic trope by celebrating the unlikely and provincial hero. Each narrative, while seemingly detached from Middle-earth, is infused with Tolkien’s linguistic playfulness, moral earnestness, and his profound belief in the transcendent qualities of story.

Furthermore, these stories reveal Tolkien’s debt to older literary traditions—medieval allegory, fairy tale, religious parable—while also showcasing his ability to innovate within them. By revisiting these forms through a modern lens, Tolkien reaffirms the relevance of fantasy literature in the modern world. In this way, Tales from the Perilous Realm becomes a quiet manifesto for the enduring value of fantasy: not escapism, but recovery, consolation, and illumination.

Positioned within Tolkien’s canon, this collection is not an appendix to the grand epics but an essential facet of his mythopoetic philosophy. It demonstrates that the perilous realm is not confined to Middle-earth, but exists wherever imagination dares to cross the threshold of the real. For readers and scholars alike, these short stories offer a window into Tolkien’s broader literary ethos—an ethos rooted in humility, spiritual depth, and an unyielding belief in the redemptive power of narrative.

- Hits: 252